Intro & Preparation

Until a few months ago, just about everything I knew about Morocco came from a Netflix special about the hashish smuggling industry with a little bit of French history and some Instagram posts from Transbike Adventures mixed in.

In September 2019, I heard about Atlas Mountain Race from an ultra-endurance athlete I met in Kyrgyzstan during the 2018 Silk Road Mountain Race. The same race director who put on SRMR was hosting a new race in Morocco. There was a website, with a little bit of information and a registration date that had already passed. The Atlas race was scheduled for February 2020, which coincided with Tour Aotearoa, another event I was considering. After having seen the Atlas mountains from Tarifa at the start of Iberica Traversa just a few months prior, I was itching to get across the Strait of Gibraltar and ride through those hashish-laden valleys. New Zealand can wait!

Here’s the teaser video:

I sent a message to Nelson Trees, the infamous race director (and accomplished ultra-endurance racer himself) asking about Atlas Mountain Race. He assured me the event was happening and that applications would open in just a few days. As soon as the registration period opened, I submitted my application and got the good news just a few days later: I had secured a position at the start line of Atlas Mountain Race 2020!

Note: Atlas Mountain Race will be providing a link to track the race once it begins on February 15th. My intention is to post the link to tracking here as soon as it is made publicly available!

Preparation:

Iberica Traversa was my “A” race for 2019, and happened to be in April. I learned in the months before heading to Spain for Iberica Traversa that it is very challenging to train for an early season bikepacking race. And Atlas Mountain Race was a few months earlier in the year than IT was.

A bit of background: I’m currently the primary caregiver for our daughter, Amelia. My wife works full-time, remotely, and I spend the day changing diapers and feeding the little one. And it is incredibly rewarding, challenging, and time-consuming. When we first decided that I’d be a stay-at-home-dad, I expected to have SO MUCH FREE TIME. I planned to start companies, create a series of bikepacking races, train until I could beat Lael Wilcox, and still have time left over to learn how to play video games.

Nope.

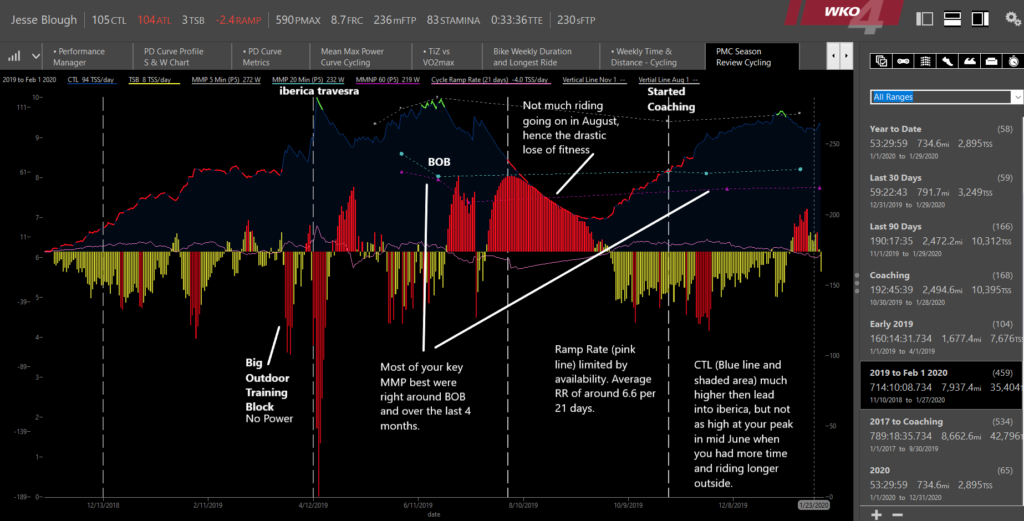

Before Amelia was born in June, I was on the bike 20-30 hours per week. From June until September, I dropped down to 10 or so, which is still fairly respectable. But the quality of my training was pretty limited, as with so few hours to train I opted to do more casual riding at lower intensity. I had a 24 hour mountain bike race that left me injured toward the end of the season, which also took a chunk out of my strength. So with limited time, I wanted to optimize the time I DID have, and maximize my improvements in the months between September and February. And one element of self-guided training that I’d always loathed was developing my own training program. It takes a LOT of time to put together a structured plan – way more time than you expect.

After careful consideration and some budget kung-fu, my wife and I made the decision to hire a coach to help me prepare for the event. I opted to work with a local triathlon and cycling coach whom I knew from the local racing scene in Bend Oregon, Mike Larsen of Larsen Performance Coaching. Mike is an incredibly strong athlete and has a propensity for positivity unlike anyone else. His reputation as a coach is that he is a hammer-head and extremely performance driven – a perfect match for me and my time-crunched weeks.

Training:

I don’t want to get too deep into my training program because training is a very subjective topic, but a lot of people ask me about it so here is a general overview. Here’s my Strava link if you want to follow me: Jesse on Strava

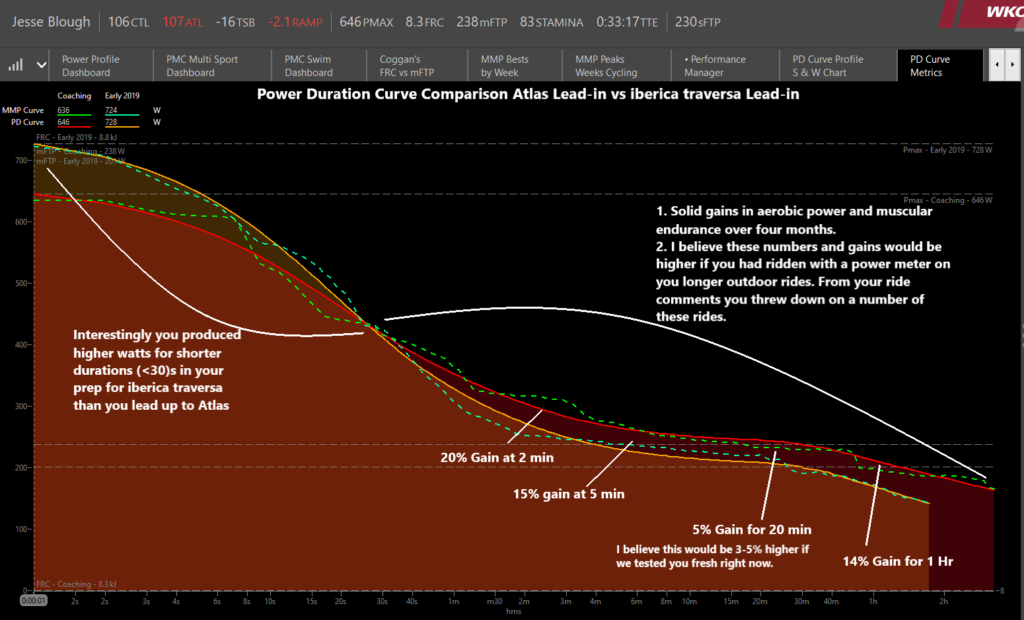

I did a four-dimensional power test in October to establish some baseline info for my coach. This test is designed to measure Neuromuscular Power (5 second), Anaerobic Power (1 minute) Maximal Aerobic Power (5 minute) and Functional Threshold Power (1 hour derived from a 20 minute block). While NMP and AP aren’t super pertinent to ultra-endurance training, they’re good info to have for a baseline. Most importantly, my FTP was an underwhelming ~230W or 3.4w/kg, though that might have been a little low due to accumulated fatigue. Using my power profile, and focusing on increasing my FTP, Coach Mike developed a program to get me closer to the 4w/kg goal I’d created for myself.

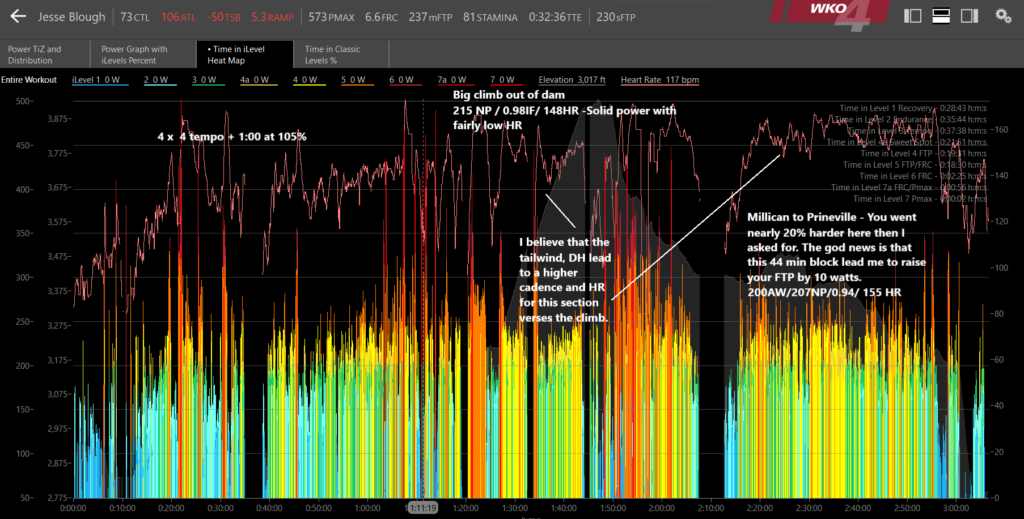

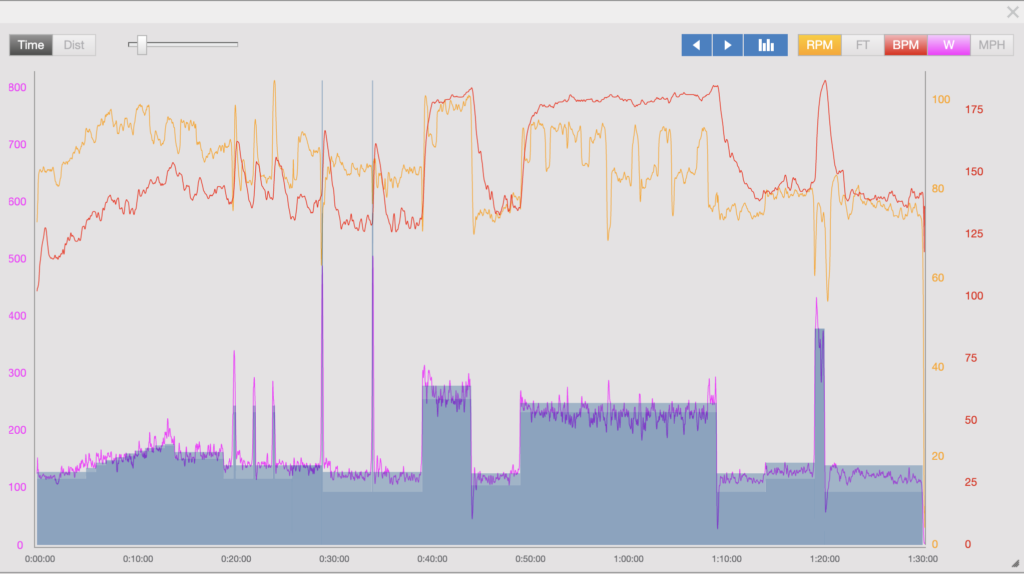

Monday thru Friday, I rode the trainer for 1-2 hours nearly every day from October until the end of January. My trainer workouts typically involve a couple of Sweet Spot (84-97% of FTP) workouts per week, lots of tempo (76-90%), and muscular endurance builds (typically involving some cadence work) from 80-105% of threshold. I spent very little time above threshold, but the intervals above threshold were usually part of pyramids or slow builds and not random, punchy sprints like in programs I’ve run previously.

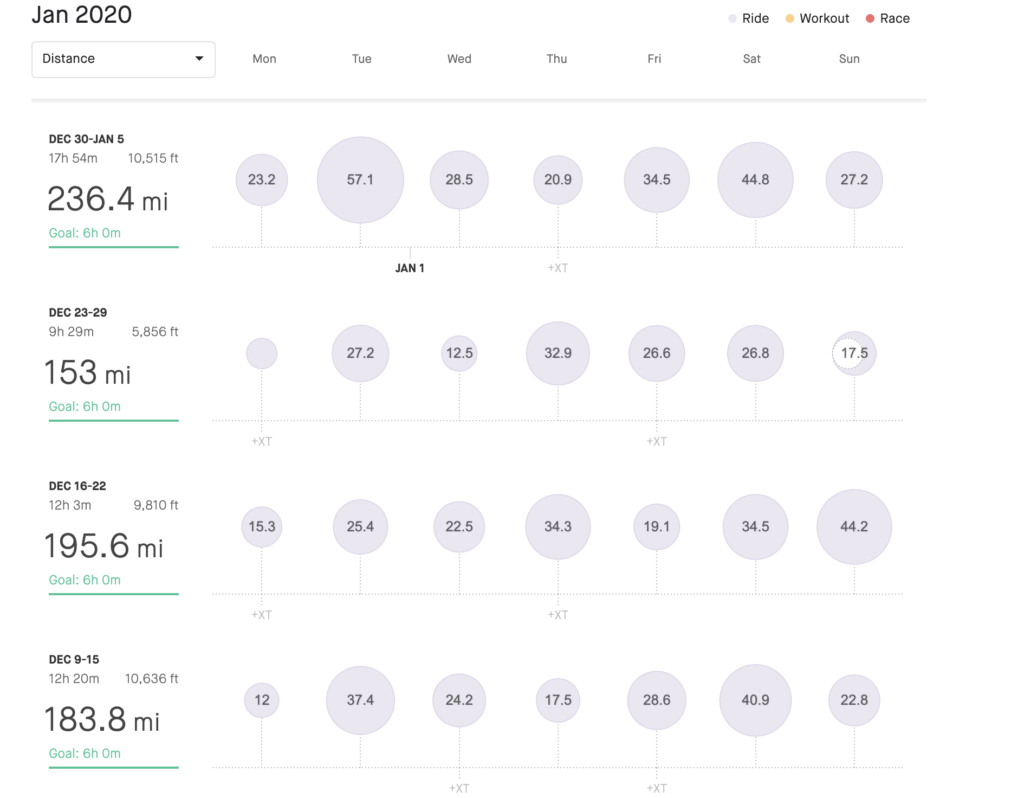

Most weekends, I was able to get out for a team ride or bikepacking trip. But I also live in the mountains, so there were certainly a few weekends where snow, bad weather, or life otherwise prevented me from getting outside. In total, I spent an average of 70 hours per month on the bike between October and February. Monday was my lightest day, on average, and Saturday my heaviest. I spent 10 days bikepacking and did not have a single ‘zero’ day of no activity. Mileage varied substantially, with 154 miles being my fewest miles in a week and 240 being my highest mileage week. Having a coach definitely improved the quality of every mile that I put in.

Recovery is a key part to any successful training plan. I chose to recover by riding at low intensity rather than not riding at all. My uneducated, anecdotal understanding of this ‘active recovery’ philosophy is that it trains the body to recover during low-intensity, sustained efforts. I’d try to keep my heart rate under 130bpm and power at less than 60%, at my coach’s suggestion. He’d probably be able to share more knowledge with you than I could.

I decided to take an indefinite hiatus from running as it has created some serious pain. A few years ago I crashed during a road race and broke my femur, and as a result I have a rod and several screws in my leg. Unfortunately, my IT band gets irritated by the hardware, and so I’ve opted to focus on cycling exclusively (read as: my ortho tells me it’s not a good idea to run ultras AND ride ultras). That sucks, because I really enjoy running and I think it is great cross-training for the bike. I did squeeze a handful of runs in during my 4-month training block, but they were unscheduled and low-effort.

I did do some strength training every week. I’m fortunate to have access to a squat rack at home (because my wife’s first love is weightlifting) and so I usually do compound lifts twice per week. Day 1 would be: Squats, Overhead Press, Bench Press, and a few accessory lifts. Day 2 looked like: Squats, Bent-Over Row, Deadlift, and accessories. Weight started low and progressed but never got very high. The goal of weightlifting was to put on some weight. I lost 15 pounds in 9 days while racing Iberica Traversa, and historically have struggled to maintain my weight during racing season. My ‘goal weight’ for Atlas Mountain Race was 150 pounds.

I don’t count calories or macros, but my diet is pretty clean and all home-cooked meals. I eat a smoothie in the morning comprised of kale or spinach, fruit, peanut butter, oats, avocado, coconut milk, and yogurt. I worked it out to around 1000kcal once and assume that’s still accurate for my serving. Lunch is usually eggs, often with meat and/or cheese and a tortilla or rice. I do a lot of the cooking in our household, especially dinner, which is usually 50% veggies and 50% protein. I’d estimate my daily intake at around 3000kcal per day during this training block. I didn’t hit my goal weight, but I did manage to put on a few pounds and I’m happy about that.

Overall I feel like my training has been solid, given the limited time I have to train. Now, I know that 10-20 hours on the bike per week is a LOT of time to most people, but relative to the elites who compete at a high level in my discipline, it isn’t much at all. In a perfect world, I’d have spent more time each day riding, and spent a lot more time bikepacking. But the quality of training (hopefully) makes up for quantity of training. Not having to create my own schedule or stress about building/revising workouts has been fantastic; hiring a coach was the best decision I could have made. I couldn’t have done it without you, Mike.

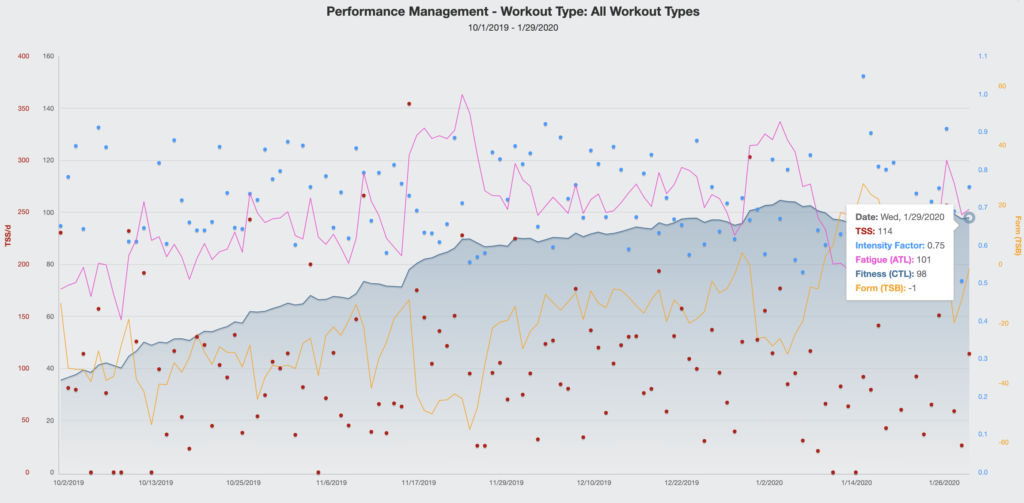

Here are a few interesting metrics from Training Peaks:

- Training dates: October 1st 2019 thru January 31st 2020 (123 days)

- Active cycling days: 120

- CTL (Chronic Training Load) on October 1: 35

- CTL on January 31: 101

- Weight on October 1: 138 pounds

- Weight on January 31: 144 pounds

- 1 hour power (FTP): 14% increase (230W to 253W)

- 20 minute power: 5% increase (though likely higher, see graph notes)

- 5 minute power: 15% increase

- 2 minute power: 20% increase

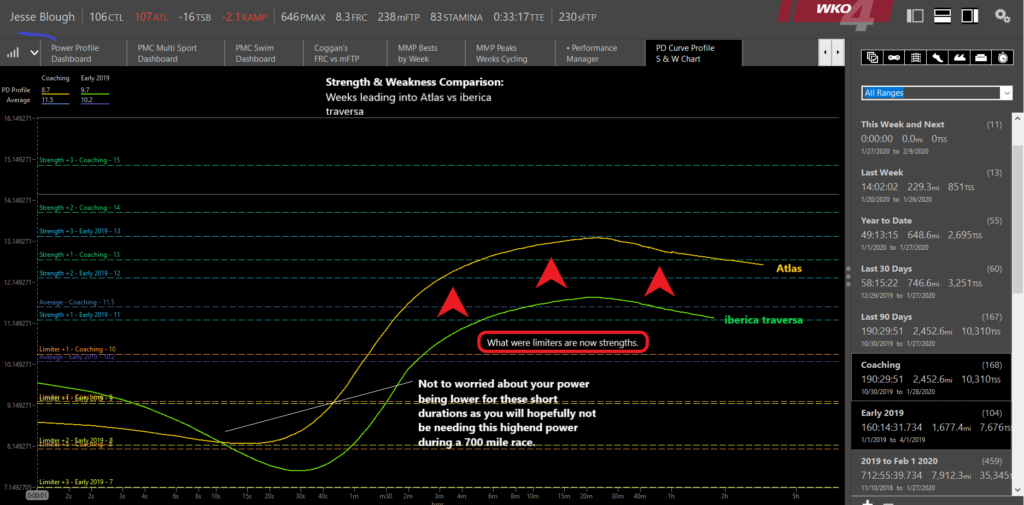

I asked Coach Mike to share a few charts showing my performance gains, and he was kind enough to do so. His notes are the text on each graph. See here: